close

What is Pelorus Foundation?

Our mission is to champion innovation and act as a catalyst, empowering individuals and local communities to preserve and protect the world’s wildlife and wild places for future generations.

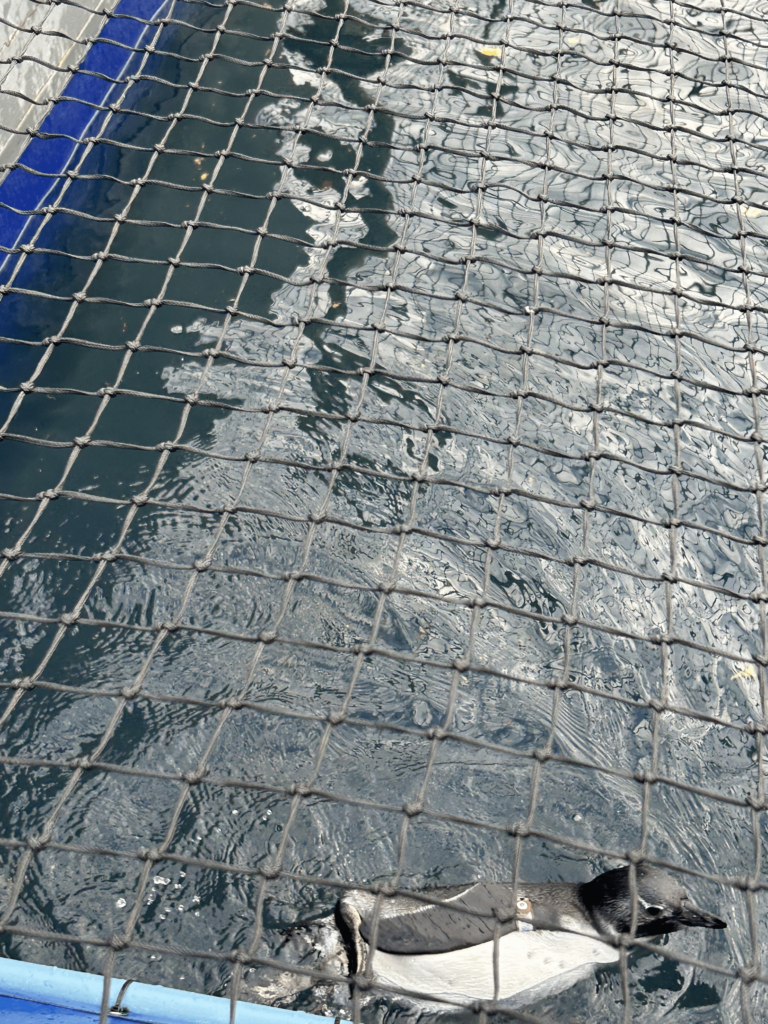

Sea bird conservation in South Africa is of paramount importance due to the country’s extensive coastline and rich marine biodiversity. Organisations like SANCCOB (Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds) lead the charge, focusing on the rescue and rehabilitation of injured and oil-affected sea birds. They also conduct vital research to better understand the needs of these avian species. Through education and outreach, they raise public awareness about the significance of preserving these coastal habitats and the species that call them home. South Africa’s commitment to sea bird conservation plays a crucial role in safeguarding these remarkable creatures and maintaining the ecological balance of its coastal environments.

Founded in 1968, SANCCOB has played a pivotal role in safeguarding various species, particularly those affected by oil spills and human interference. Their mission is to ensure the survival of these precious avian creatures through rescue efforts, medical treatment, and educational outreach. In addition to their hands-on work, SANCCOB places a strong emphasis on education and public awareness. Through various outreach programs, they aim to engage and inform local communities about the importance of preserving coastal bird species and their habitats. By instilling a sense of stewardship and environmental responsibility, SANCCOB empowers individuals to take an active role in the protection of these magnificent creatures.

One of our contributing writers, Lana Jevremovic, helped out for a day at SANCCOB and sat down with staff to discuss what local sea bird conservation looks like in South Africa.

I started working at SANCCOB in 2017 in the education department as an intern, then moved into rehabilitation. I did that for a year and then I think I missed the education aspect of the job, engaging with different people across work. That for me is what brings passion to my life and it’s what I do now which is amazing.

I’ve always loved all animals in general. You know, growing up I was sort of one of those people that always knew I had to work with animals one day.

So, we’ve got firstly different areas that you could intern in. We’ve got education, rehab, chick rearing unit, nursery for bigger chicks.

Depending on which department, there are specific goals and responsibilities. In the rehab department, we start out with the basic skills, which is just the general daily cleaning that needs to be done and then we move on to intermediate tasks such as handling birds and learning how to feed them, as well as differentiate between them and their specific needs. Afterwards we move to the barn, which is more your ICU specialised unit, where you would work closer to the vet team to treat injured or sick birds.

We have different areas on the property and each one is split into the type of species that you are working with and the level of care that they need. So depending on where you are in your rotation, you’ll be required to either train in that area or if you are skilled in that area already you get sent to a different one.

At the moment we mainly have African penguins, and we have received an influx of chicks earlier this year so there is a specific skillset required for that – which is something we need to build up.

We also have Cape gulls, cormorants, Hartlaub’s gulls, Cape gannets, and not too long ago we had an albatross, although we don’t see those as often.

There’s a specific skillset that is required to take care of the animals so that is something we do need to build up. However the main thing is, with a wide variety of birds, you need a wide variety of skills and that is not something that you can pick up easily.

Its even trickier when we accept a lot of international volunteers which later go home, even though some volunteers end up being hired at the end of the internship, retraining new people every other month can be time consuming.

Handling chicks requires a different level of skills so when there is an influx, we call on those who have had previous experience with them. Unfortunately, the reason they came in was due to the flooding during the weeks of storms we had.

Once we get the chicks into the centre and they are placed in the specific area depending on their age and health, it’s easy in terms of getting them the treatment they require. However, any chick that comes into the centre has to go through the program to ascertain what state they are in. They have to be able to swim for an hour, have to be waterproofed etc. Some take a bit longer, especially if they need waterproofing.

Some will be released back into the wild relatively quickly, others require a bit more time. So its really on a case-by-case basis, based on a series of assessments that we do.

You know they are sufficiently waterproof when, after swimming for an hour, the down layer of feathers are completely dry. When chicks grow into juveniles, they shed their fluffy fur and grow into their first set of waterproof feathers. It’s something they can lose and get back. Things like blood or oil condition their feathers regularly in order to achieve waterproofing – if the bird is lazy, they will not attain it or perhaps even lose it.

Its about three to three and a half months, it’s not that long if you consider the entire life of the bird, which can be up to 27 years.

Yes with any rehabilitation work that is one of the main concerns, which is why we have a lot of strict rules in place in terms of what we wear in front of certain species and the way we touch them, to the kinds of sounds that we play in the CRU unit to try and simulate their wild environment, but unfortunately we cannot totally avoid this issue. It is part of rehabilitation, but also definitely an area to be monitored just to make sure the treatment will not have a negative to their reintroduction in the wild.

The steps we take to avoid this issue are:

If, despite our efforts, we find a bird has been accustomed to human contact upon release and is returned to the facility, there are several options that we will try for that bird. Mainly, we wouldn’t re-release them in such a public colony where there are lots of people passing by. We would rather try a release on a remote island colony where there are not many people – however these areas are monitored by one of our monitors to ensure they are safe and successfully integrating into the colony.

We give each one of our penguin patients a transponder – a little microchip used to monitor their movements. It is not active tracking, rather passive. If ever we have researchers doing work on the colony they use this to gather info regarding their activities. Also across colonies, we have scanners which are basically pipes that the birds walk over and scan them without impacting them. This also gives us info on what times certain birds are leaving the colony, or if they have switched colonies.

There is so much involved there so these are really just the basics. Essentially, we want to monitor if what we are doing is really working – how are these birds behaving, how are they doing once released?

Yes, it provides a lot of important information for us but also for the people who support us as well.

For instance, our CRU unit, which has been operational for 15 years, has results that prove that our birds, being hand-reared at the facility, are surviving as well as the wild birds. So that shows us that we are making a difference

Adults are different, once an adult has paired up with a mate, it is very difficult to separate. However, with the younger birds who haven’t, they are not bound to a colony yet so they would just wonder around until they find a suitable colony and eventually find their mate. That is why we are able to work with researchers, to assist in setting up their new colony. For example, towards the Eastern Cape, we have just established a new colony in a nature reserve. We release the young ones in the hopes that when they are ready to mate and pair up, they will use that site as their colony and establish a new one. We are in the early stages as it takes a couple of years, but we are getting there.

One of the main issues from my perspective is the lack of commitment from our local database, because those are the people that are able to assist in crisis situations. Having the commitment to stick to the program, stay involved after it – even just at the minimum. Then ideally set up and progress to more advanced tasks.

Secondly, we lack financial support from local communities and business sectors. Since we are a non-profit, we don’t receive regular funding from the government which makes it tricky to have these operations running 365 days a year. Especially the mass treatments required this year due to the chick influx.

There’s been quite a few and a lot of them have been related to the response to crisis events or disasters which for me just shows the passion and the combination of the staff and anybody involved. That is something I feel proud to be a part of. It’s no joke taking in over 700 patients at one and spending weeks on end rehabilitating these birds in preparation to release them in the wild. I’m really proud of this, we have a great release rate. Not a lot of other organisations can say that.